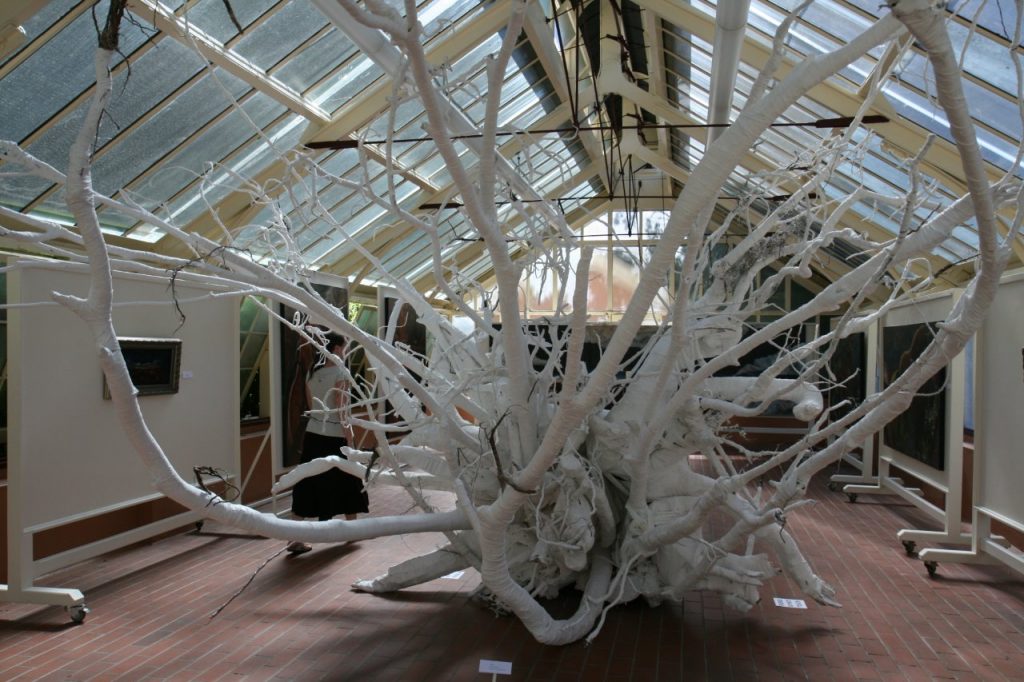

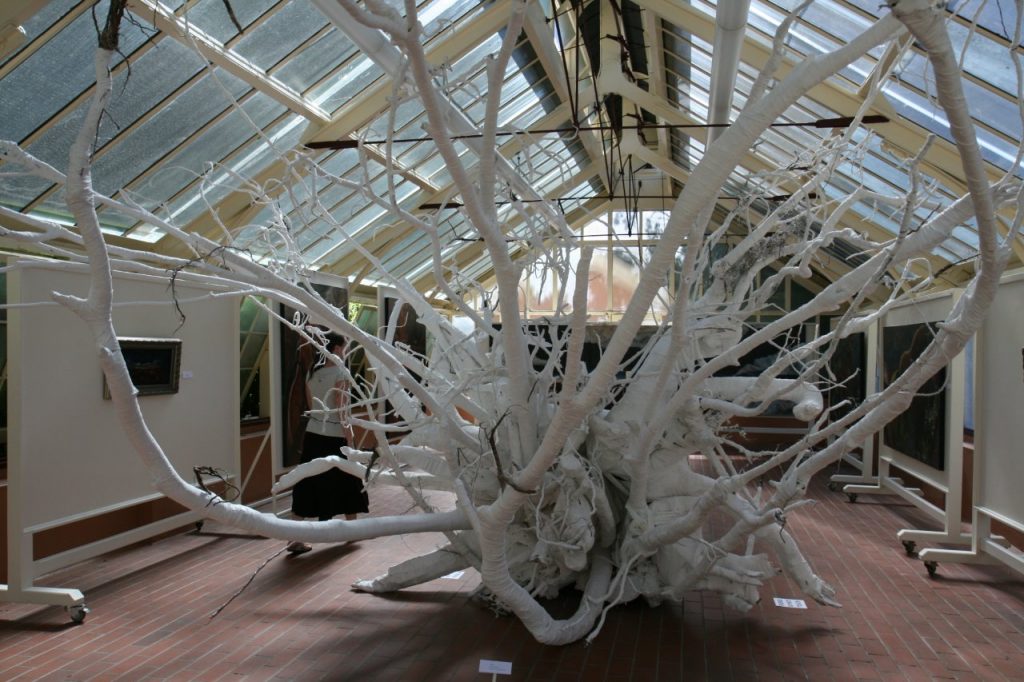

Paintings and installation, The Palm House, Royal Botanical Gardens 2009

The Royal Botanic Gardens of Sydney can be seen as a symbol of European invasion/colonisation of Australia. By its very nature it is home to botany from around the globe, introduced species that have been transplanted to a new environment, hence displacing indigenous flora and fauna.

This exhibition comments on the displacement and physical/cultural dismembering that forms part of the discourse of Australian occupation. The work relates not only to the original inhabitants of Australia, but also the global diaspora.

Unrooted encompasses both the experience of being uprooted – those who have lost their roots – and the inability of putting down roots, of connecting with the new environment – those that have no roots in this land. White man got no dreamingi, no ancestral spiritual connection to land. It is this connection to land and the grief of losing it/experience of not having it that I am exploring.

“To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognised need of the human soul” ii The land is used as a metaphor for the harm done to the displaced.

In this exhibition landscape is treated as an agent to observe historical scars. Australia has been seen as a land to be taken. A target. The aerial view, a military view, a view of migration, a land of dreaming.

Like the colonisation of America the settlers “cut loose from the earth’s soul, they insisted on purchase of its soil, and like orphans they were insatiable. It was their destiny to chew up the world and spit out horribleness that would destroy all primary peoples”iii

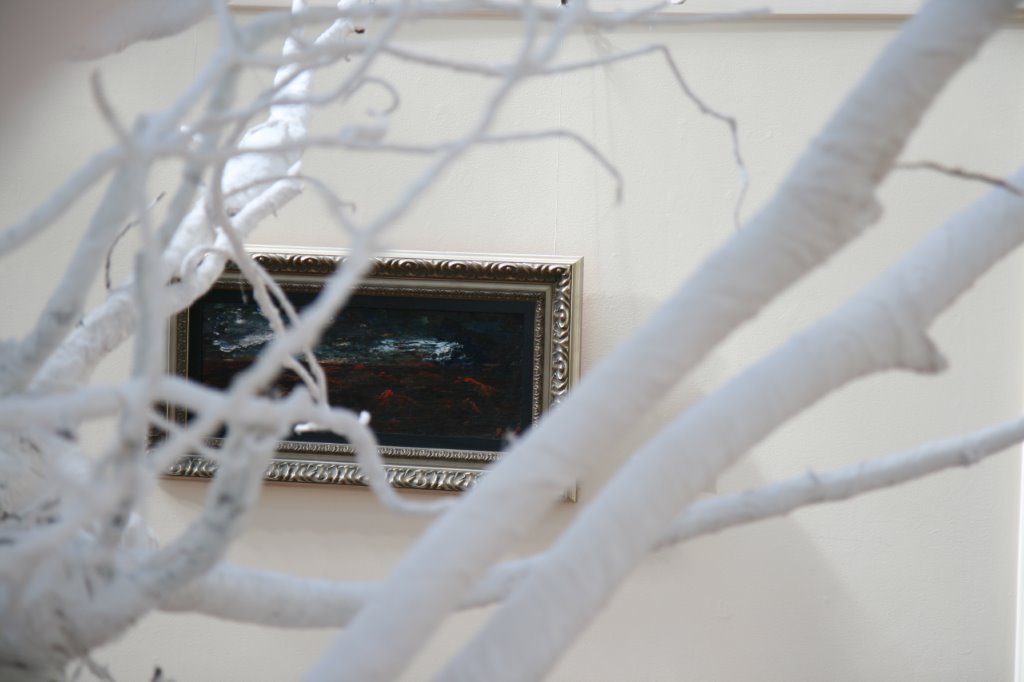

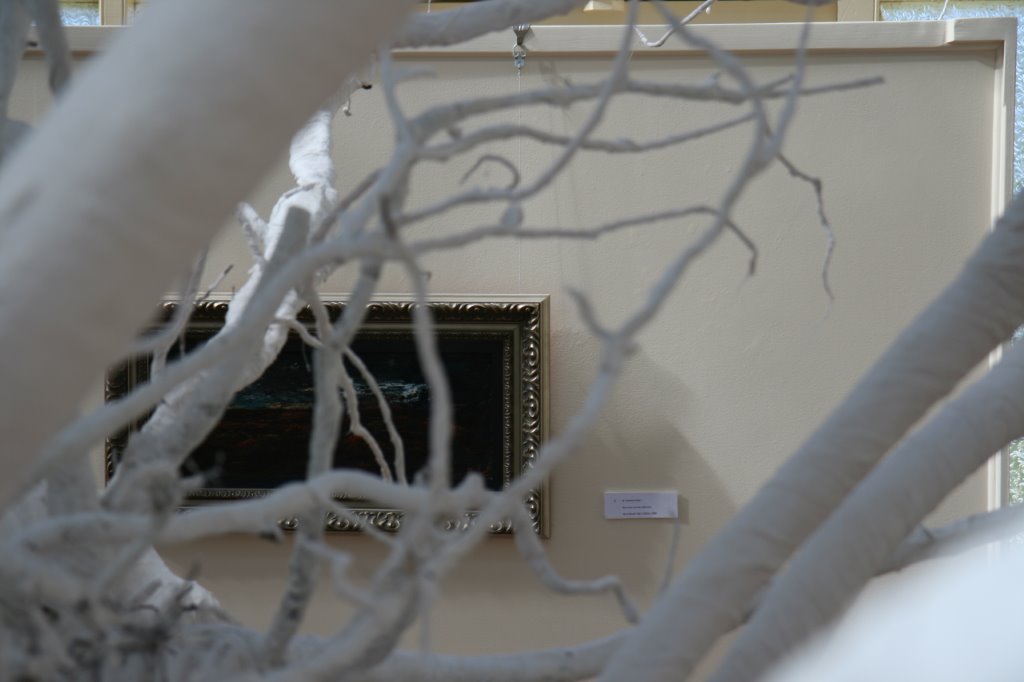

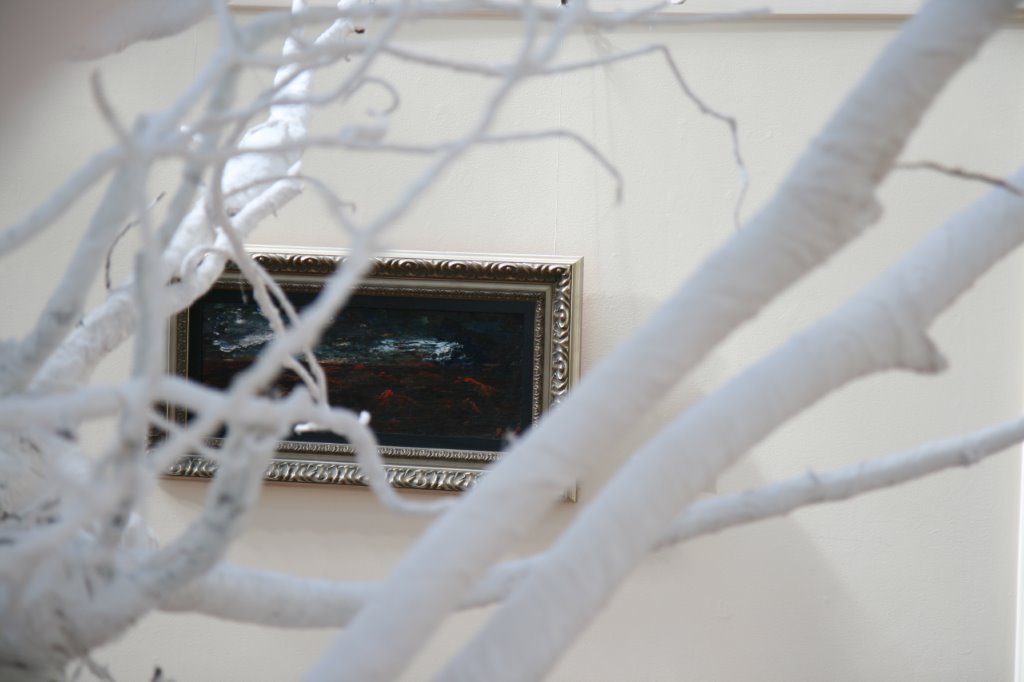

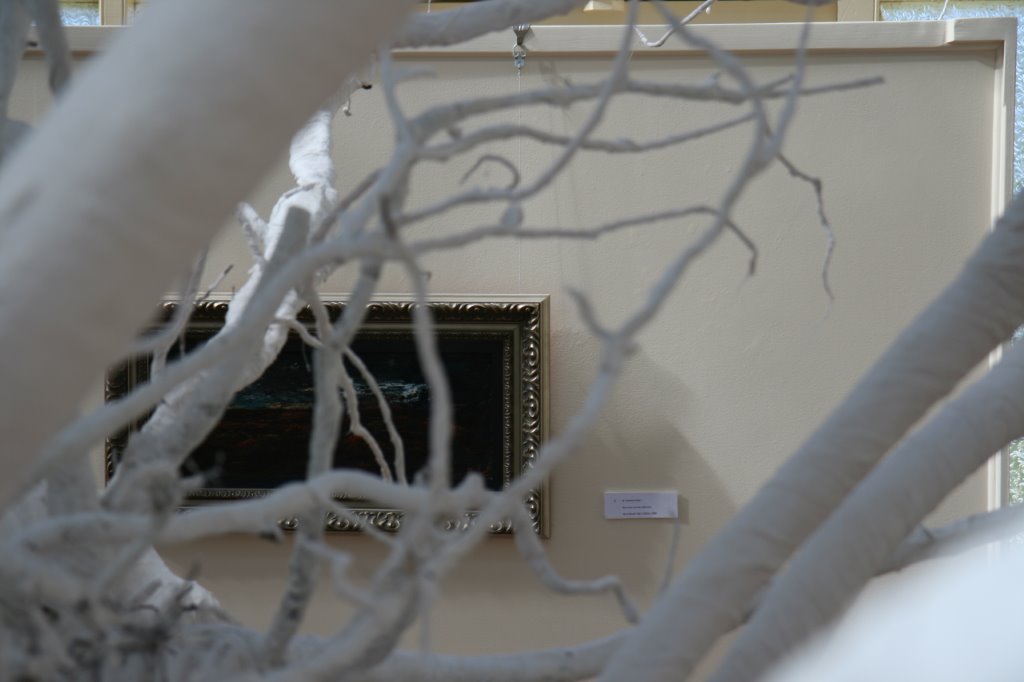

In preparation for this exhibition I was shocked at how many people did not know of the history of Myall Creek and Appin, this to me is symptomatic of the social amnesia that Australia continues to suffer. Like the traditional framing of the small landscape works, containing/controlling the landscape painting, the viewing of the land and its history through a glided frame still takes place today.

Gilded framing provides a frame of reference for the viewing of these landscape paintings in which the landscape is void of its true history. A framed view goes hand in hand with the appropriation of landscape, a reference to the relationship that the West has with land itself – fenced, controlled, commodified.

To quote one of Australia’s prime ministers, the Honourable Robert Menzies, “The more you see of contemporary art in other parts of the world the more proud of Australian art you become… none of our leading artists produce freak pictures and our landscapes show the sunshine and sheep of the Australian scene” iv

The use of satellite images as a source for paintings places the viewer into an existing /real landscape, locating the viewer on the globe, is in the world, in this country and therefore into the veracity of its history. Figurative paintings show mythological human figures against epic Australian landscapes.

The installation comments on the hope intrinsic to the healing process. A fallen tree, synonymous with death, of cultural and social dismembering, is in the process of healing, healing of historical scars – both human and environmental.

1 Stanner W. E. H, White Man Got No Dreaming : Essays, 1938-1973 ,Canberra, Australian National University Press, 1979

2 Simone Weil, The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration towards Mankind, London, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1952.

3Morrison, Toni. A Mercy, London, Chatto & Windus 2008 P.52

4The Hon. Robert Menzies, 1937. Cited Mike Parr Sydney Bienale 2008